In the spring of 2013, I came across a dusty old manuscript at my mother’s house in Somerset. It turned out to be my grandfather’s memoir, written about his experiences during the Great War. Reading it was quite a revelation. Not only was it dramatic and well written, but also a fascinating historical document, providing a thorough and vivid description of life in a WWI German PoW camp – an aspect of history that has, I have subsequently discovered, been little explored by historians. I decided to try to have it published, hoping that it might appear in print while the author’s daughter, my now 85-year-old mother, was still around to read it. I am pleased to say that the memoir – ‘Escaping from the Kaiser’ by Herbert Tustin – has just been published by Pen & Sword Books, much to the delight of my mother.

My grandfather’s memoir begins with him in Northern France in April 1915, en route to the Second Battle of Ypres with his regiment, the 8th Durham Light Infantry. He describes how the initial mood of ‘glorious adventure’ gave way to much darker emotions as they neared the battle zone and the grim realities of war become ever more apparent. The 8th Durhams were sent to the most critical section of the allied line, the extreme head of the Ypres Salient. Outgunned and outnumbered, their position was hopeless. The regiment was decimated by the German bombardment, and those that survived were forced into a desperate retreat, during which my grandfather was captured, along with a great many of his comrades.

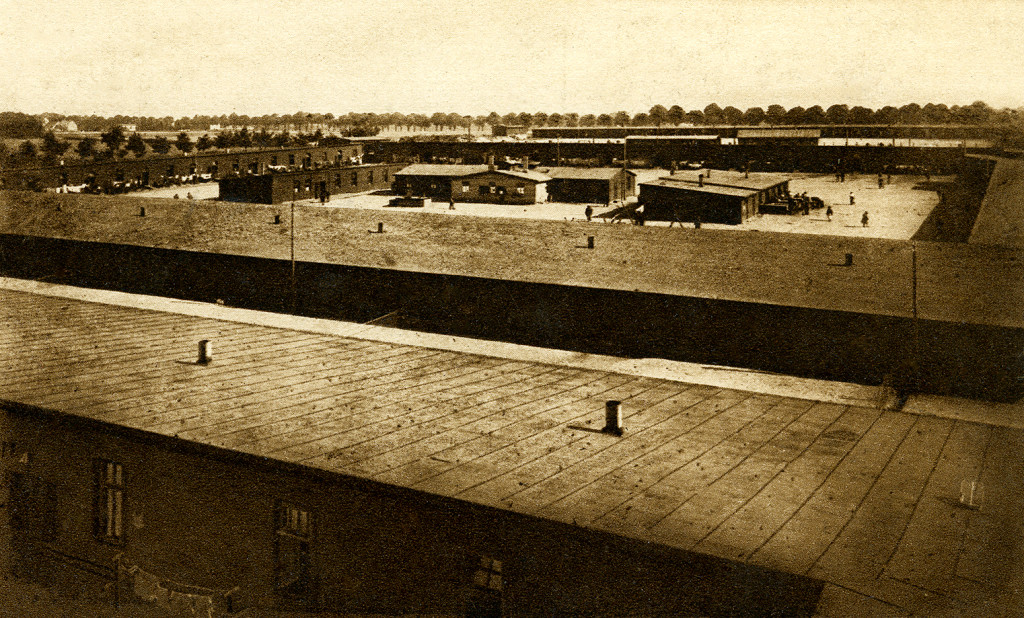

Following capture, my grandfather and his fellow captives endured an arduous three-day rail journey in cattle trucks to Rennbahn PoW camp, just outside the German city of Münster. Here he was to spend 16 months, and a large portion of his memoir is devoted to describing this experience in great detail: the hunger, hardships and brutalities; the prison work; the character of the various nationalities; the activities and recreations; and the friendships and humour.

Conditions at Rennbahn were tough, but my grandfather made the best of the situation, participating in many of the prisoner-organised activities, including accompanying at the piano for theatrical productions, playing the organ during church services and helping to edit the PoW church magazine. Nevertheless, thoughts of escape ran constantly in his mind. According to a recently acquired recording of an interview with his friend and 8th Durham comrade, Private William Stephenson (1894–1995), my grandfather decided to escape because he got word that a ‘young lieutenant’ was paying too much attention to his sweetheart Sybil, which troubled him greatly and made him determined to return to England as soon as possible. He had met Sybil, who was to become his wife, while they were both trainee teachers at the College of St Hild and St Bede in Durham, and their relationship was kept alive during the war through a frequent exchange of letters.

Whatever mix of emotions inspired my grandfather, they must certainly have been very strong, as attempting to escape was an incredibly risky venture: Rennbahn was surrounded by a triple girdle of barbed wire, with the middle wire carrying a lethal electric charge. Armed guards were posted at every entrance, and watch-dogs patrolled the perimeter fence, which was illuminated by powerful arc lamps. Any would-be escapee who succeeded in breaking free from the camp still needed to cross 50 miles of enemy territory before reaching the safety of neutral Holland. In addition to these formidable difficulties, my grandfather had the sobering knowledge that all previous British escape attempts had failed, and that he would be severely punished if caught. Finally, as if he needed reminding of the dangers, within less than a month of making his own bid for freedom, a French prisoner was shot and killed in the act of attempting to escape.

My grandfather’s first effort to escape was by tunnelling out of the camp. He and an 8th Durham comrade, Private Thomas B. Dickinson (called ‘Hicky’ in my grandfather’s memoir), also an alumnus of Bede College, took over a tunnel that had been abandoned by other prisoners. They set to their digging work with great enthusiasm, but the increasing moisture and stench, which they suspected was coming from the camp sewers, forced them also to abandon the tunnel.

Not to be defeated, in the summer of 1916, my grandfather conspired with Canadian PoW Gerrie Burk on an alternative plan: this involved cutting the wire beneath one of the entrance gates, which were not electrified but kept under constant armed guard. The idea was to choose a stormy night, wait for the sentry to disappear into the shelter of his box, less than four yards from the gate, creep up, cut the wires and crawl beneath the gate to freedom. It is difficult to see how this audacious plan could have succeeded, but the fact that they were resolved to carry it out says a lot about their determination and courage.

Fortunately, they came up with a better plan: on the pretext of visiting some sick friends, they inveigled their way into the camp hospital, which was just outside the main camp and away from the electric wire. Here they were helped by their PoW friends, one being Private Alfred J. Cleeton (of the 7th Canadians), who by good luck had befriended the watch-dog and was thus able to keep it at bay. Seizing their moment and with the sentries only yards away, the intrepid duo made their dash up and over the ten-foot barbed wire, lacerating their hands horribly in the process, before making good their escape.

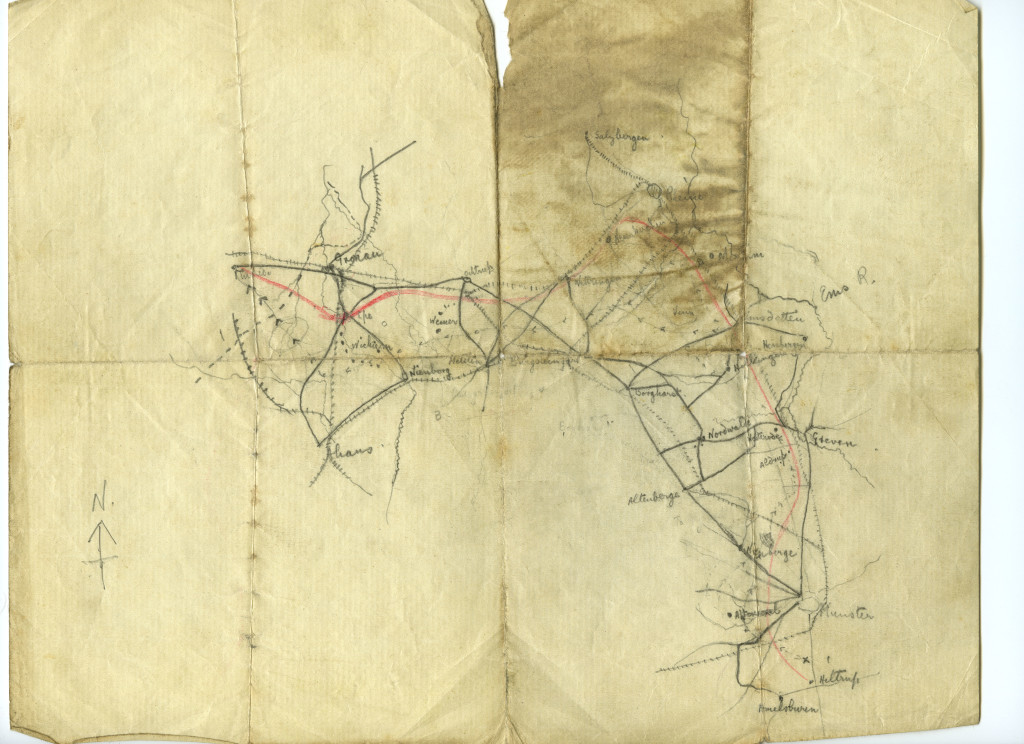

For the next nine days they headed for Holland, travelling by night and hiding during daylight hours. Increasingly weak and hungry, they supplemented their small food supply with whatever they could find – wild berries, vegetables foraged from fields and apples stolen from orchards. Each day of their nerve-wracking journey brought new dangers: roving hunters, barking dogs, road blocks, treacherous bogs, children at play and even run-away bulls – all of which threatened to expose their presence and bring their dreams of freedom to an abrupt and inglorious end. Somehow, they managed to avoid recapture, despite the closest of calls. Exhausted almost beyond their ability to continue and only yards from neutral territory, they were met by a fusillade of shots fired at them by German frontier guards. Luckily, it being night-time, they managed to evade the guards and, finding sanctuary in a ditch, crawled slowly forwards, inching past a German sentry before finally crossing the Dutch border to safety and freedom.

On arriving in Holland, they were relieved to meet a friendly group of soldiers, who accompanied them to the nearby town of Enschede. The Dutch authorities, having verified their story, treated them with the utmost kindness and sent them under escort to Rotterdam, where the British Consul arranged their passage on the first boat leaving for England. Their voyage was a perilous one, for the previous four ships to leave Rotterdam had been torpedoed by German U-boats. Fortunately, their vessel, the SS Grenadier, was able to navigate its way across the mine-strewn, submarine-infested North Sea, to arrive safely in Newcastle on Tyne on 18 September.

My grandfather’s amazing story of war, imprisonment, survival and escape, enhanced by original photographs, concludes with an epilogue by my grandmother. Writing some 20 years after her husband’s death, she recalls his welcome home, the joyful reunion and his proposal of marriage.

Sadly, I never knew my grandfather, whose life was cut short when he died of cancer in 1939. I am grateful, however, that he left such a dramatic and wonderfully written wartime memoir. Having it published has been something of a personal tribute, and I am proud to be related to a man who showed such courage under so much adversity. I am also delighted that that his story – ‘Escaping from the Kaiser’ by Herbert Tustin – is now available to be read and enjoyed by everyone.

We would like to express our sincere appreciation to Richard Corr [grandson of Herbert Tustin] in supplying this article for the Northumberland At War Project.

![Patients and Staff Outside the Sanatorium c.1920s [HOSP/STAN/11/1/54]](http://www.northumberlandarchives.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/HOSP-STAN-11-01-54-300x192.jpg)