March is Women’s History Month giving us an opportunity to shed light on some of the lesser-known stories of women from our archive. When researching family history, it is common to know what our grandfathers and great-grandfathers did during the Second World War but not many know what their female relatives did during the war. Now, more than ever, it is important to share the stories of those who lived through life changing experiences so that they can be remembered, and others can come forward to tell their own – ensuring they won’t be lost in time. Held in our archive are several collections relating to women during the Second World War. Here is Linda’s story told through her photos and books from our archive and library (she wrote her books later in life).

Linda was born in 1918 to a mining family and grew up in Ashington, living on Station Road then moving to Ashbourne Crescent. In the 1930s the family moved to Eleventh Row then to Dene View in the 1940s. Before the war started, Linda worked in Hirst Grocery, which was part of the Ashington Co-operative Society – she had lots of competition to get this job as she explains in one of her books. At the outbreak of war, in 1939, Linda voluntarily joined the Ashington Air Raid Precautions (ARP), completing an anti-gas precautions test followed by assisting in the recruiting of other women for the service. In her book, ‘From Store to War,’ she describes how she felt when asked to help with recruitment, “I had never felt so important in the whole of my life.”

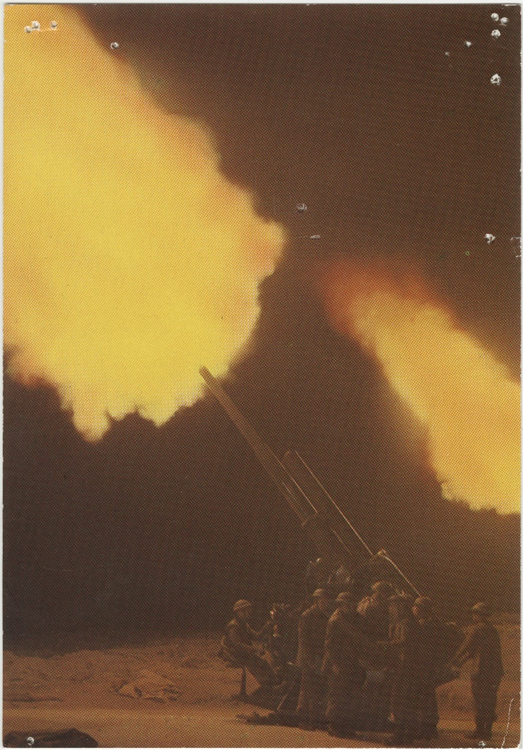

By early 1940, Linda was volunteering as an ambulance driver around Ashington, where

she was given an old black ford to use as an ambulance, working evenings and weekends

(like many volunteers, they worked their day jobs in addition to these voluntary posts). She

remembers in her book, “There, at my post, often in total darkness and often cold, I sat

gazing at the searchlights and the occasional flashes and being grateful for the Ack-Ack

(anti-aircraft) pounding away defending with all their might this particular corner of our vast

empire.” During her time as an ambulance driver, she only ever took one casualty to

hospital when a land mine fell on Lynemouth one night, injuring a man in his garden. While

trying to take him to Newcastle’s eye hospital, she broke down once and lost a car door on

the way there! She did, however, get him safely to the hospital.

In October 1942, Linda was called up for service – the conscription of women was

introduced in December 1941 – joining the Auxiliary Territorial Service (ATS). In her book

she says she spent her last day of civilian freedom at a cinema in Blyth where they were

showing Gone with the Wind. She illustrates a vivid picture of the day she left, “Dearly

loved autumn, full of colour and changing pictures, trees beginning to show their dark, lacy

structure against the pale sky, gardens browner than they were, the dew still throwing up

diamond patches on the dark grass. Carrying my suitcase, I scuffed and crunched my way

among the leaves that had fallen from the park trees. At the bus station I met up with

Evelyn Todd. She too was going into the Auxiliary Territorial Service.”

Soon after she was sent to Fenham Barracks where she got her uniform. Like many other

women found, the uniform didn’t fit very well, and she eventually took it to a seamstress to

be altered. Very early into her time with the ATS, she caught Scabies, staying in the sick bay

for a while until she was better. By the time she was ready to leave, she had been told she

had a high IQ and that she would do well in RDF (radar) which would mean working as

close to active service as possible (working on anti-aircraft stations). Across her career in

the ATS, she was promoted to Lance-Corporal, ‘making her a number one’ as she mentions

in her book then transferred to the Army Education Corps where she rose to the rank of

Warrant Officer. Whilst being in the ATS inspired her to become a teacher after the war, the

journey that took her there was risky and dangerous at times.

In 1944, Linda was working not far from London when the threat of V2 rockets challenged

the radar stations, as they were undetectable before they hit. It was when Linda was on

leave in London, however, that she experienced the destruction of these weapons. When

making her way back to a train station to return to camp, the air raid siren sounded. She

hurried back but was stopped by a warden when a bomb fell near them, knocking them

both to the ground. Shaken, she tried to continue but was told to find shelter in a nearby

hut. She describes, vividly, in her book, “There was a loud whistle, the earth shook, toppled

and crumbled. Bricks, it seemed, were raining down. I stood still in a little protected

pocket. I felt my body all over and my face. I was all right.” The warden nearby helped her

out, amazed that she was alive – many weren’t so lucky in the 1944 blitz on London using

V1 and V2 rockets with over 30,000 civilian casualties and hundreds of thousands left

homeless [1].

Linda described, in her book, an incident at her radar station caused by a power outage

where she had to carry a box to an FFI Mark II plane waiting outside. She describes, “I

hesitated just a moment. All hell was let loose. The noise was deafening. The searchlight

stilts criss-crossed the sky. The lights from the tracer shells. The planes overhead and the

bursts of flame. The fires. The flares. It wasn’t the thought of a bomb that frightened me.

What terrified me was the thought that I wore no hat and any second now a small piece of

shrapnel might come down and pierce my skull ending the life I knew. I ran as quickly and

carefully as I could, panting not from exertion but from the effect of the raid.”

[NRO 07023/2/3/3]

Linda’s experience in wartime changed the course of her career. She talks openly in her

book about questioning the expectation of getting married and settling down after the war,

debating the options of studying and returning to her old life. At the end of the war, she

decided to join a teacher’s training course in Newcastle, completing her training at the

University of Ireland. She married her husband, Ernest, in 1948 and enjoyed a rewarding

career for the rest of her life. In the 1960s, she and her husband ran a boarding school for

girls in Worsley, Manchester, which accommodated over 100 girls. Linda pioneered sex

education in schools and presented radio programmes about human relationships. Her

first book, ‘The Pit Village and the Store’ was published in 1985 and some parts of her

books were dramatised by Channel 4 (even featuring Linda in some of the shop scenes).

After the war, many women returned to their old jobs or domestic duties, as encouraged by

the government. In 1939, around five million women were employed but by 1943, over

seven million were employed due to the war. By 1951, women’s employment had almost

returned to the pre-war level and a bar on married women working continued in many jobs

[2].

Bibliography:

[1] Imperial War Museums, The Terrifying German ‘Revenge Weapons’ Of The Second

World War Blog – The Terrifying German Revenge Weapons Of WW2 | Imperial War

Museums (iwm.org.uk)

[2] BBC Teach, GCSE History resources – Did the war change life for women? WW2: Did the

war change life for women? – BBC Teach

Book referenced –

From Store to War By Linda Mccullough-Thew (1987)

Linda’s other books –

The Pit Village and the Store: Portrait of a Mining Past (1985)

A Tune for Bears to Dance to (1992