As Northumberland is the most northerly English county the history of its manors is tied very closely to Scotland and its history. War has shaped the fortunes of many manors, but this is also the case with cooperation between the two countries. The connection between them is local, not just national, and Northumberland’s manors have played a role in that history. The whole picture is far too detailed and interesting to deal with in a short blog post, with so many wars, conflicts, rebellions and raids, but we can look at what impact the relationship had on the way manors were run and the terms they used.

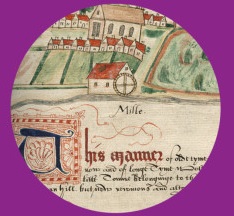

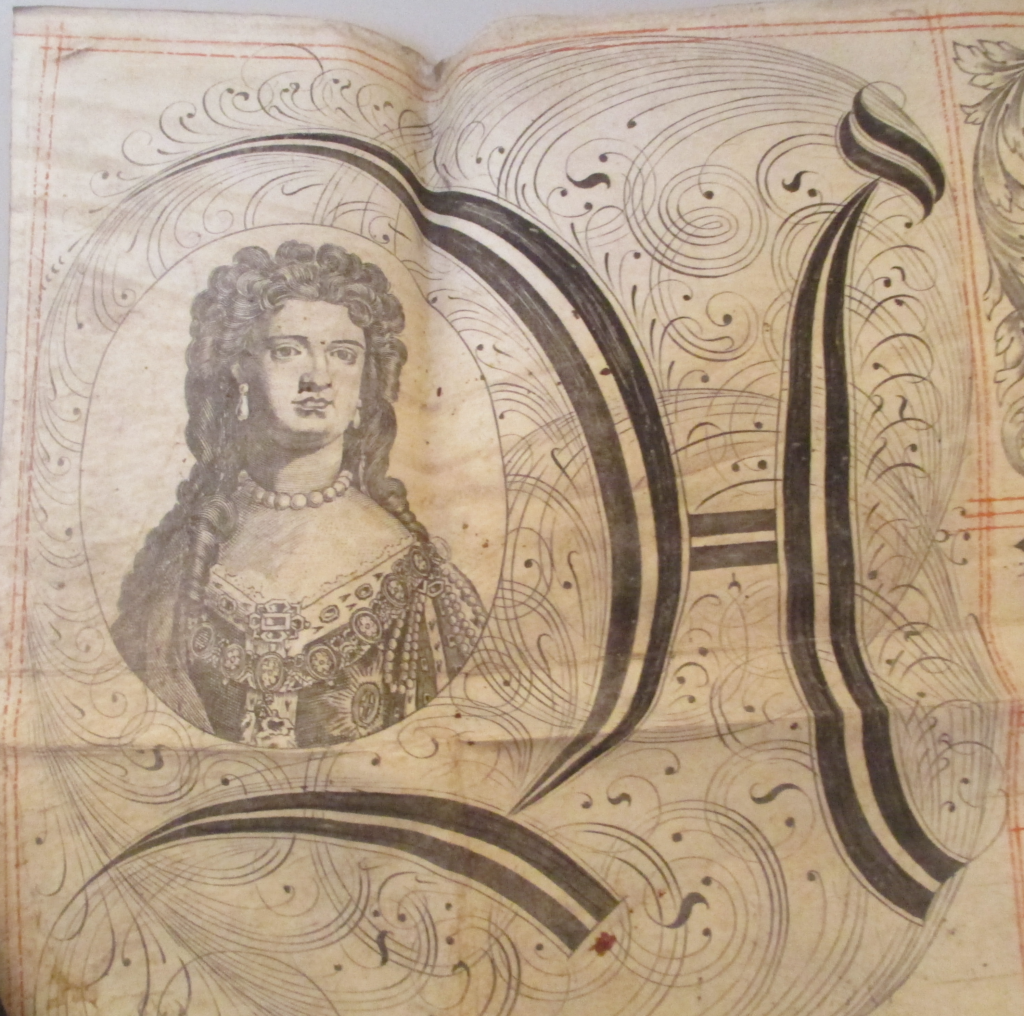

Early in manorial history many manors were owned by the Scottish Kings and noblemen. For example in 1279 the kings of Scotland rented two thirds of Bellingham Manor to the Bellingham family by a Serjeanty, or condition, where the Bellingham family acted as the king of Scotland’s forester in Tynedale forest. Eleventh and twelfth century conflict between the countries changed this ownership. The king of Scotland’s portion of the manor was seized by Edward I during war with Scotland and was later given with other lands to Edmund earl of Cambridge, later duke of York, by his father Edward III. Edward III forced the Scottish king and nobles to give up the southern counties of Scotland in 1334, and nobles forfeited their estates in England, including Patrick V earl of Dunbar whose manor of Middleton Hall was granted to Henry Percy.

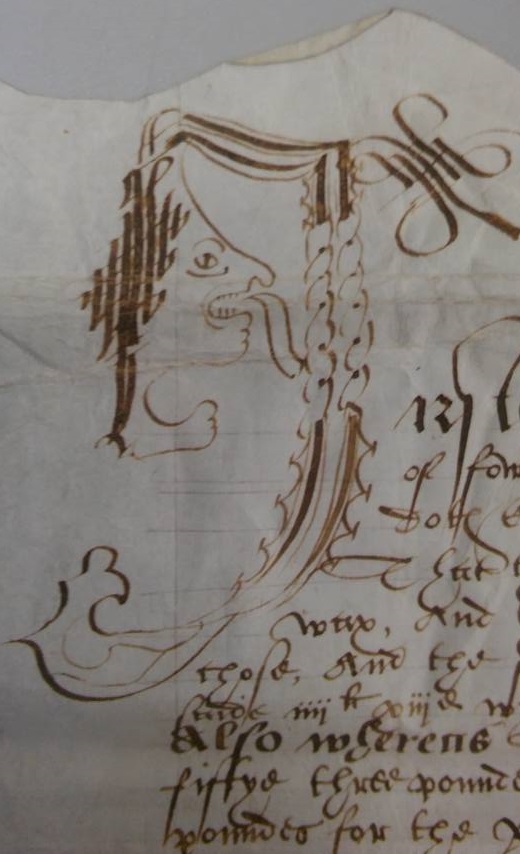

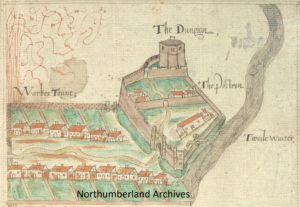

Warfare damaged the crops in many manors, bringing no income for the lord of the manor and famine for the inhabitants. A number of manors were expected to provide soldiers and equipment in peace and war, such as Corbridge which had to provide one man! A lawsuit of 1579 over a small holding at Burton shows that land tenure in Northumberland still came with a requirement to serve in protecting the border. Peles and other fortified dwellings were often built by the lords of manors for safety. Even manors a good distance from the border were vulnerable, with Longhoughton described as ruined and waste after wars in 1368, and from cattle raids in 1573. Border reivers operated from both sides of the border, and watches would be kept for reivers in many places. One example from the Order of watches in 1552 shows a night watch was kept between Hitchcroft in Shilbottle to Rugley in Alnwick by ten men from Shilbottle, Whittle, Sturton Grange, Birling, High and Low Buston, Wooden and Bilton townships.

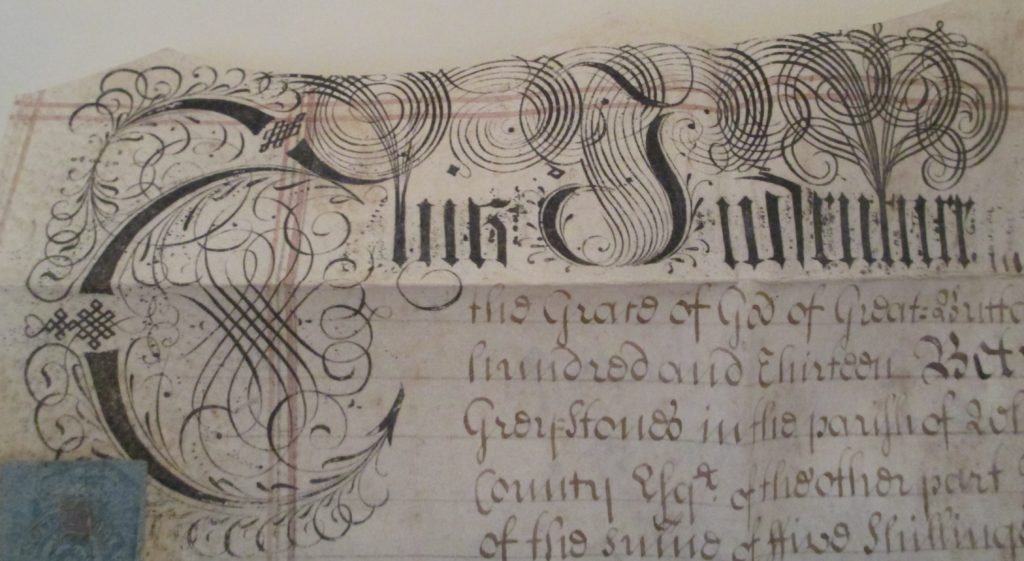

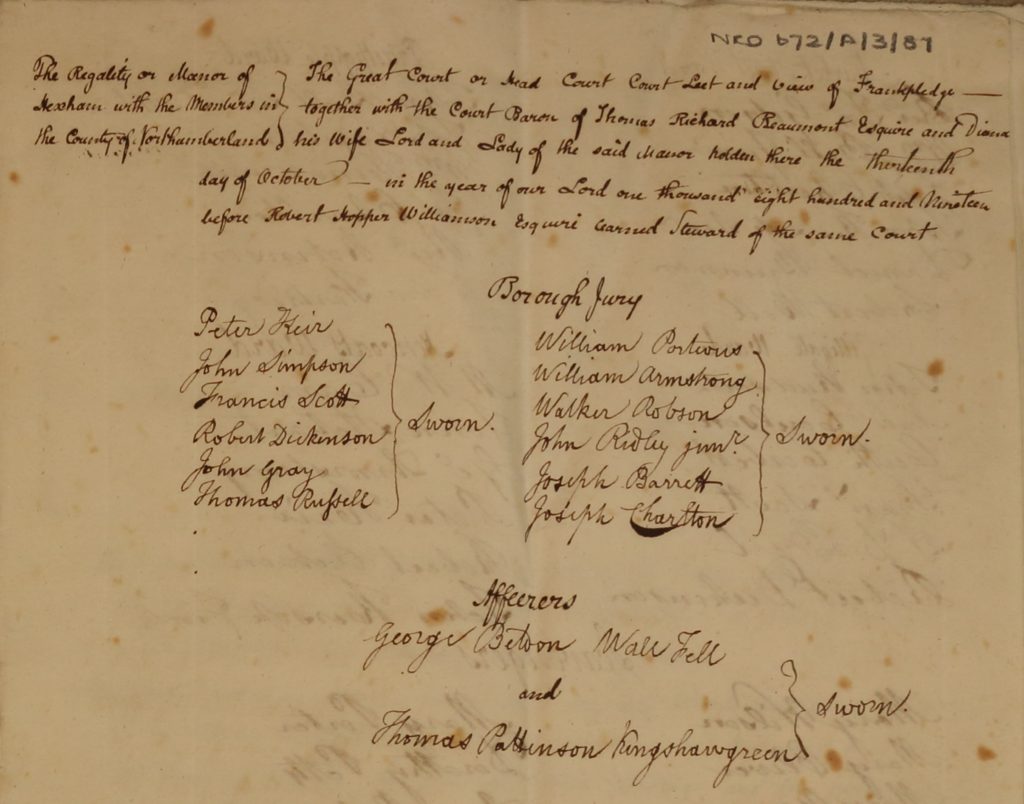

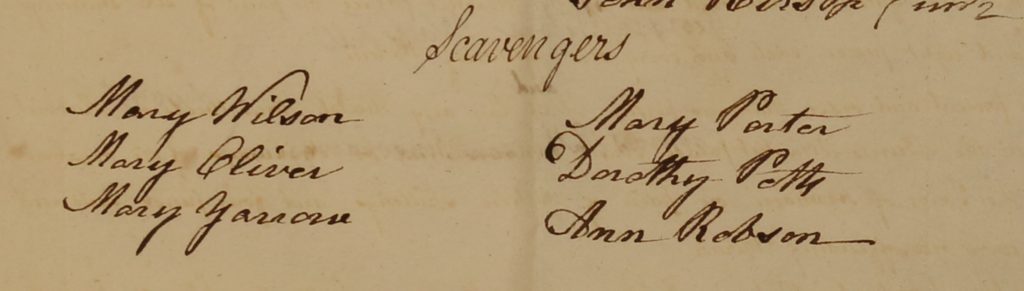

However it is the everyday business in manorial documents that show the connection – Scottish law and terminology was sometimes applied across the border. We have below a few Scottish terms we have found in the manorial records.

We found ‘Grassum’ was paid in what is known as the West Water manors (the manors of Melkridge, Henshaw and Ridley & Thorngrafton). This was paid every 21 years from 1758-1885 for some of the leasehold tenements, and recorded in one book for the purpose (ZBL 66). Looking at a few Scottish law sources this can be a sum paid by a tenant at a renewal or grant of a lease, or a single payment made in addition to a payment such as rent or feudaty. It might be comparable to the English term premium. It is hard to say why Grassum would have been paid there, or for how long the practice was carried out. The key may be right back in the early history of the manors, when they were owned by the Kings of Scotland and leased to a number of noble Scottish families such as the earls of Athol and earls of Badenoch.

As covered in a previous post, there were numerous jobs associated with the manorial court, and Scottish roles were similar to many in the English manor courts. For example in Norham, now a small English village on the banks of the River Tweed overlooking Scotland, we find the Scottish term ‘Land liners’ used. Within Scottish burghs, as in the English equivalent, Boroughs, the inhabitants (burgesses) were entitled to a ‘burgage plot’ of land. Whilst in an English manor a ‘fence-looker’ would check the legality of such boundaries, in Scotland and Norham, the term ‘land liner’ was used for this official who measured out and checked the size of the burgage plots.

Our project is continuing to compile the history of each manor at a time and through doing so will be continuing to post about the interesting terms and stories we find.

The Northumbrian County Histories Volumes I, V, and XV have been of great use in the preparation of this blog, as have The Concise Scots Dictionary and Law Basics: Glossary of Scottish Legal Terms (O’Rourke and Duncan).