We have covered a little about how law and order was kept by the manorial system when we looked at customs in a previous blog, but what about crimes that broke laws, not just customs? The manorial court or court Leet met around twice a year and dealt with minor boundary issues and scuffles. Most manor courts, though not usually recording such punishments, seem to have kept stocks, pillories and tumbrels for punishing those guilty of smaller crimes. Stocks trapped the prisoner around the ankles, while a pillory held them around the neck and wrists. In both the prisoner would be further subjected to abuse and refuse thrown from the crowd. The tumbrel was a two-wheeled manure cart, which would be used to transport the prisoner and perhaps tip them into a pond – the practice often referred to as ‘ducking’. Tuggal Manor was fined 1 shilling 8 pence in 1683 for not keeping a pair of stocks. Presumably they would have been a common sight as you travelled around the country, and some towns like Berwick still have theirs on display.

However in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries a manorial court could, with royal permission, become a franchised law court dealing with more serious cases, and we have found evidence of a few of these as we have been researching the manor authority files. The whole picture of medieval law is too complex to delve into in a short blog post, but the various parts of the machine can be grouped into three types of legal administration: the central courts of law; different types of smaller courts held by itinerant commissioned justices as they progressed around the country; and permanent local franchise courts. The franchise of the legal responsibility for a particular area might be given by the crown to a hundred, borough, or the feudal courts of the Court Baron or manorial court. Some lords held the ancient right of ‘infangthief’ and ‘outfangthief’, where if they caught thieves from within or from outside the manor red-handed on their land, they could try and fine them. Those whose manor was franchised held royal permission to maintain a gallows and tumbril to execute anyone found guilty. This was possibly a hangover from the Anglo-Saxon period where nobles held this right, and was continued by the Norman monarchy. In 1294 Woodhorn Manor had licences for its own gallows. The Barony of Embleton, held by a succession of powerful Lords, also had very extensive privileges. In 1292 Edmund Earl of Lancaster held the Barony, and claimed the right to decide in his court pleas similar to those tried before the sheriff. He had a prison at Embleton and gallows at Newton, Embleton, Dunstan and Craster. Though one of the lesser Baronies of Northumberland, the Barony of Langley owned by the Tindale family held this ancient liberty to try thieves in the Leet Court and then hang them on their own gallows.

This right was also claimed by Gilbert de Umfraville, who maintained a tumbril, pillory, toll and gallows in his manors of Harbottle, Elsdon, Ovingham and Whelpington. However he was questioned over some of these rights. In 1275 his neighbour Walter of Sweethope complained that after border disturbances Umfraville had imprisoned him in Harbottle Castle and demanded a fine of 100 marks and even after Edward I had taken Sweethope under protection Umfraville damaged his property. In 1279 a long list of charges was brought against Umfraville by the Assize judges (some of the itinerant judges who brought different courts around the country). He was accused of hanging prisoners, unlawfully extracting fines, and acting as sheriff within his liberty. On this occasion the jury acquitted him. In 1293 Gilbert was ordered to prove his right and show the warrant by which he could imprison, hold prisoners’ property and return all writs issued to him by the king. He claimed he held an ancient right, given before the time of Richard I. Did he really hold the ancient right of infangthief and to have a gallows, or was he taking advantage of a judicial system that allowed certain persons these rights? Though infangthief was useful for peacekeeping on a dangerous border, nothing prevented a powerful lord from abusing these powers.

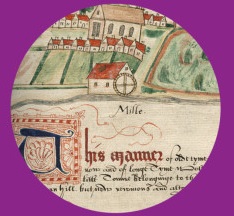

The franchise courts dwindled over the centuries as the royal courts were more attractive for freehold tenants, especially those whose problem was with the lord of the manor. By 1461 franchise courts had lost the right to even present serious cases to the royal courts. The legal system underwent great changes through the fourteenth century, shifting to a central rather than local control, but we can still find where gallows stood in the landscape from old maps and place names. They were often placed on high visible points, as at Gallowhill near Bolam where the Bolam barony executions took place, and Gallowshill near Hartington where the Bolbec barony gallows stood. If you have come across any other examples of private gallows we would love to hear of them.

References:

Bailey, M., (2002) The English manor

Harvey, P.D.A., (1984) Manorial records

Jewell, H.M., (1979) English local administration in the middle ages

The Northumberland County Histories series

1 thought on “Private stocks and gallows – crime and punishment in the Manor”