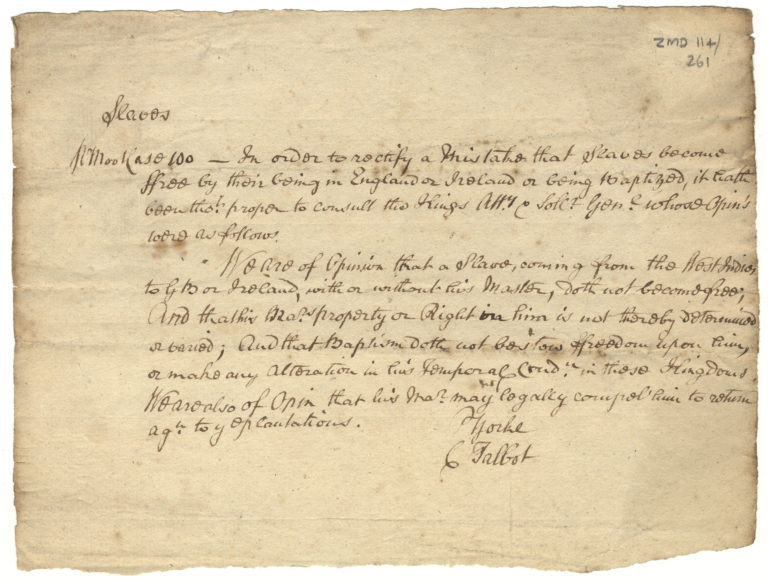

Yorke-Talbot Opinion, 1729

Reference: ZMD 114/261

Suggested age groups: KS3, KS4, Lifelong Learners

Subject areas: Black Presence

CONTEXT

In 1661 Barbados introduced the first “Slave Code”, officially named “An Act for Better Ordering and Governing of Negroes”. The Code defined people of African origin on the island as chattels – they were the property of slaveholders, to do with as they wanted. The Code gave the holders of enslaved people the right to punish, torture and kill them. Other British colonies in the Caribbean and mainland Americas introduced similar Slave Codes.

The legal status of people enslaved in the British colonies was not clear if they were brought to Britain by their slaveholders. It was a generally held belief that “the air of England was too pure for slaves”; the condition of slavery was contrary to everything that Britain stood for. In 1729 a group of plantation owners asked Sir Philip Yorke, the Attorney General, and Charles Talbot, Solicitor General, to clarify this legal position.

Yorke and Talbot wrote the opinion as can be seen here in the document and transcript. They did not offer any further justification or quote any other sources.

The Yorke-Talbot opinion stated that enslaved people who came to this country were not automatically freed. Enslaved people who were baptised did not become free. It was also a generally held belief that Christians could not be slaves. They also stated that if an enslaved person was brought to this country they could be sent back to the plantations against their will.

James Somerset (sometimes Somersett) was an enslaved African-American man from Virginia. His slaveholder, Charles Stewart, transported him from Boston, Massachusetts to England in 1769.

While in England, Somerset was baptised on 12 February 1771 (a copy of the parish register can be seen by searching London Metropolitan Archives’ “Switching the Lens” database – see link below). Towards the end of 1771, Somerset ran away from Charles Stewart, but was soon recaptured. Steward then arranged for Somerset to be shipped to Jamaica where he would become a plantation worker.

Somerset’s friends (and god-parents) applied for him to be released from the ship and brought before a court (using a writ of Habeas Corpus). Somerset approached Granville Sharp about helping argue his case in January 1772.

Since 1765 Granville Sharp had been working with run-away enslaved people in London. He taught himself law (he was not a trained lawyer) so that he could argue for the release of people in this country. The Yorke-Talbot Opinion was used by his opponents to prove that Africans continued to be the property of their slaveholders in this country.

James Somerset’s case tested out the legal arguments that Granville Sharp had been developing, including those against the Yorke-Talbot Opinion. After months of debate, the Lord Chief Justice, Lord Mansfield, concluded that James Somerset could not be transported forcibly to the Caribbean and should be freed. Mansfield’s ruling is seen as pivotal in the history of enslavement in Britain and its colonies. However, he did not state that slavery was illegal in this country.

This phrase appears on the top left of the document. In legal terms it means a case dealing with an abstract question or a judgement on a right before that right has been applied in practice.

Nr Moot Case 100 – In order to rectify a Mistake that Slaves become

ffree by their being in England or Ireland or being Baptised, it hath

been thot proper to consult the Kings Atty & Sollt Gen & whose opin’s

were as follows

We are of Opinion that a Slave coming from the West Indies

To GB or Ireland, with or without his Master, doth not become free;

And that his Mars property or Right in him is not thereby determined

or varied; And that Baptism doth not bestow ffreedom upon him,

or make any Alteration in his Temporal Condn in these Kingdoms

We are also of Opin that his Mar may legally compel him to return

agn to yeplantations.

Yorke

Talbot

Number Moot Case 100 – In order to rectify a mistake that slaves become

free by their being in England or Ireland or being baptised, it hath [has]

been thought proper to consult the King’s Attorney and Solicitor General and whose opinions

were as follows:

We are of opinion that a slave, coming from the West Indies

to Great Britain or Ireland, with or without his master, doth [does] not become free;

And that his master’s property or right in him is not thereby determined

or varied; And that baptism doth [does] not bestow freedom upon him,

or make any alternation in his temporal condition in these Kingdoms

We are also of opinion that his master may legally compel him to return

again to the plantations.

Yorke

Talbot

ACTIVITIES

ACTIVITY 1

Background

The legal status of people enslaved in the British colonies was not clear if they were brought to Britain by their slaveholders. It was a generally held belief that “the air of England was too pure for slaves”; the condition of slavery was contrary to everything that Britain stood for. In 1729 a group of plantation owners asked Sir Philip Yorke, the Attorney General, and Charles Talbot, Solicitor General, to clarify this legal position.

The Yorke-Talbot opinion stated that enslaved people who came to this country were not automatically freed. Enslaved people who were baptised did not become free. It was also a generally held belief that Christians could not be slaves. They also stated that if an enslaved person was brought to this country they could be sent back to the plantations against their will.

SEE

See: What was the legal status of enslaved people from the British Colonies who had been brought to Britain by their slaveholders prior to 1729?

See: Who was Sir Philip Yorke?

See: Who was Charles Talbot?

See: Who asked Yorke and Talbot to clarify the legal position of enslaved people who had been brought to Britain from the British Colonies by their slaveholders?

See: What did the Yorke-Talbot opinion state?

See: Who was James Somerset?

See: Who was Granville Sharpe?

See: What was the reason for the Somerset case?

See: What was the outcome of the Somerset case?

THINK

Think: What were the motivations for writing the Yorke-Talbot opinion?

Think: Who benefitted from the Yorke-Talbot opinion?

Think: What precedent was set by the Yorke-Talbot opinion?

Think: What does the need for the Yorke-Talbot opinion suggest might have been happening in Britain?

Think: Why might this document have been needed?

Think: What might this document suggest about opinions of British people towards enslaved people and Black people in the country?

Think: What is contradictory about this document alongside the belief “the air of England was too pure for slaves”.

Think: How did Granville Sharpe undermine the Yorke-Talbot opinion and question its validity?

DO

Do: Discuss the opinion “the air of England was too pure for slaves”. What might this have meant? Are there different ways this could be interpreted?

Do: Discuss the paradox of British people being involved in slavery abroad but believed slavery was contrary to everything Britain stood for. Does this imply that British people were aware that slavery was wrong?

Do: Discuss the contradiction of the Yorke-Talbot opinion stating that baptism did not free enslaved people, while it was believed that Christians could not be slaves.

Do: Look at this document alongside the parish register entry for William Wandoe. What can you infer from these documents? What do they tell you about the experiences of Black people in Britain at the time? Think about the use of the words “servant” and “slave”.

Do: Imagine you are Granville Sharp. Write your argument against James Somerset being transported to Jamaica. Think about how you would challenge the precedent set by the Yorke-Talbot opinion.

Do: Research the short- and long-term impact of the Somerset case.

Do: Research the laws in Britain around slavery following the Somerset case leading up to the abolition of slavery.

Resources

https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/pathways/blackhistory/rights/slave_free.htm

https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/pathways/blackhistory/rights/docs/state_trials.htm

https://eachother.org.uk/slavery-somerset-v-stewart-oldest-50-cases/

http://www.mirandakaufmann.com/common-law.html

https://spartacus-educational.com/REsharp.htm

https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/pathways/blackhistory/rights/slave_free.htm

ACTIVITY 2

Background

In 1661 Barbados introduced the first “Slave Code”, officially named “An Act for Better Ordering and Governing of Negroes”. The Code defined people of African origin on the island as chattels – they were the property of slaveholders, to do with as they wanted. The Code gave the holders of enslaved people the right to punish, torture and kill them. Other British colonies introduced similar Slave Codes.

SEE

See: When was the first “Slave Code” introduced in Barbados?

See: What was the official name of the Code?

See: What did the Code define people as African origin as?

See: What did the Code give the holders of enslaved people the right to do?

THINK

Think: What were conditions like on enslaved plantations in the Caribbean?

Think: What was a “normal” day like for enslaved people on plantations in the Caribbean?

Think: How hard and physically demanding was it to work on a plantation?

Think: How were enslaved people on plantations in the Caribbean treated?

Think: What were enslaved people on plantations in the Caribbean punished for?

Think: How regularly were enslaved people on plantations in the Caribbean punished?

Think: Were enslaved people on plantations in the Caribbean allowed to communicate with each other?

Think: How do we know about enslaved people’s experiences on plantations?

Think: How was the experiences of enslaved people on plantations in the Caribbean preserved?

Think: How did enslaved people use music and dance to communicate their experiences?

DO

Do: Look at the images of Caribbean plantations on the Runaways website. What impression does this give you of the plantations?

Do: Make a word cloud of words that you would use to describe life on an enslaved plantation based on the images.

Do: Write a paragraph using your word cloud to describe life on an enslaved plantation from the perspective given in the images.

Do: Research what life was like for an enslaved person on a plantation in the Caribbean. Make a word cloud of words used to describe their living and working conditions, and experiences.

Do: Use the words from your word bank to rewrite your first paragraph, showing the realities of what life was like on an enslaved plantation.

Do: Listen to, or read the lyrics of, Calypso music. What do the songs tell you about the experiences of enslaved people?

Do: Research how Calypso music is used today to comment on political injustice.

Resources

https://www.bbc.co.uk/bitesize/guides/z732pv4/revision/3

https://runaways.gla.ac.uk/minecraft/index.php/slaves-work-on-sugar-plantations/

https://jamaica-gleaner.com/article/entertainment/20171001/we-have-met-songs-and-sights-slaves

https://marinabudhos.com/the-music-and-dance-of-sugar-work

https://dizzannebillyblog.wordpress.com/2016/10/10/songs-from-the-sugar-fields/

OTHER ONLINE RESOURCES

The National Archives website (archived – no longer live), page about York-Talbot Opinion and Somerset Case: https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/pathways/blackhistory/rights/slave_free.htm

https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/pathways/blackhistory/rights/docs/state_trials.htm

The National Archives Education website, page with lesson about slavery using primary sources, includes a “History Hook” video: https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/education/resources/slavery/

Spartacus Educational, page about Granville Sharpe: https://spartacus-educational.com/REsharp.htm

Spartacus Educational, page about “The British Empire and Slavery”, includes extracts from formerly enslaved people: https://spartacus-educational.com/USASafrica.htm

Each Other website (human rights journalism website), page about Somerset Case: https://eachother.org.uk/slavery-somerset-v-stewart-oldest-50-cases/

Runaways website (Glasgow University), home page (includes database of newspaper adverts for runaway enslaved people): https://www.runaways.gla.ac.uk/

Miranda Kaufmann website, page about common law and enslaved peoples: http://www.mirandakaufmann.com/common-law.html

London Metropolitan Archives website, page for “Switching the Lens” database: https://www.cityoflondon.gov.uk/things-to-do/history-and-heritage/london-metropolitan-archives/about-lma/switching-the-lens-project