Over the course of the two phases of our Wellcome Trust funded project we have catalogued, conserved and digitised over 5000 patient medical files, as well as other records and photographs. In this time we hope we have taken an inaccessible, uncatalogued collection and made it accessible to study. In our final blog we will take a look back at what we have done in that time.

Phase one conserved and digitised 949 discharge books, catalogued these, the patient files and the rest of the collection, and digitised a whopping 14671 radiographs (taken of only 2245 of the patients!). The team also created our online exhibition, our exhibition banners, and attended conferences to publicise the collection. You can read more about the first phase in the team’s final blog here.

After the Wellcome trust kindly granted more funding for a second phase new team focused on the 4095 patient files, which had been catalogued.

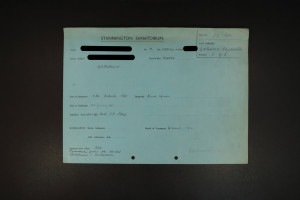

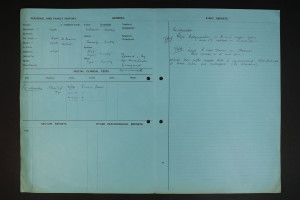

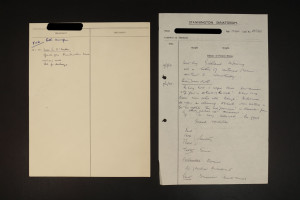

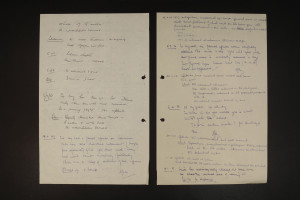

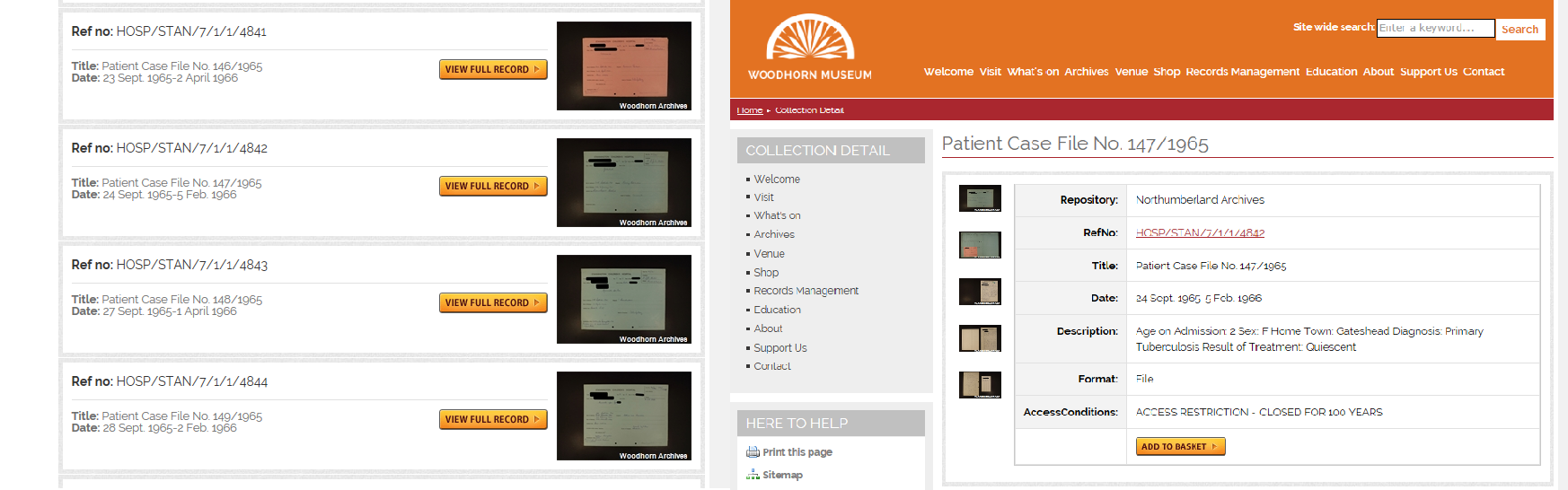

We conserved and digitised these, and redacted images were attached to our searchable online database. As they are closed records the names and addresses cannot be released, but this enables those researching the disease to access medical information about the cases for the ‘core’ documents. Here is how these look.

As we could not digitise the entire files in each case the team decided to upload some examples on Flickr. Though there is no such thing as a ‘typical’ or ‘average’ Stannington file, we tried to choose a few redacted examples of the patient files that gave an impression of the collection as a whole, and the type of documents found within them. You can view these here.

The work began in phase one to raise awareness of the collection has continued. We have continued to blog about our progress and discoveries we have made about the collection, the sanatorium itself, and new collections that relate to it, such as May Brown’s the Atkin family’s photographs. There has been academic interest in research projects using the collection from a number of universities, which we hope to will continue to grow.

Our former colleague Rebecca Cessford is using the collection of radiographs and patient files in her PhD thesis to look at the potential as an aid to diagnose the disease in skeletal remains. You can find out more about her research in the blog she contributed to us on World Tuberculosis Day.

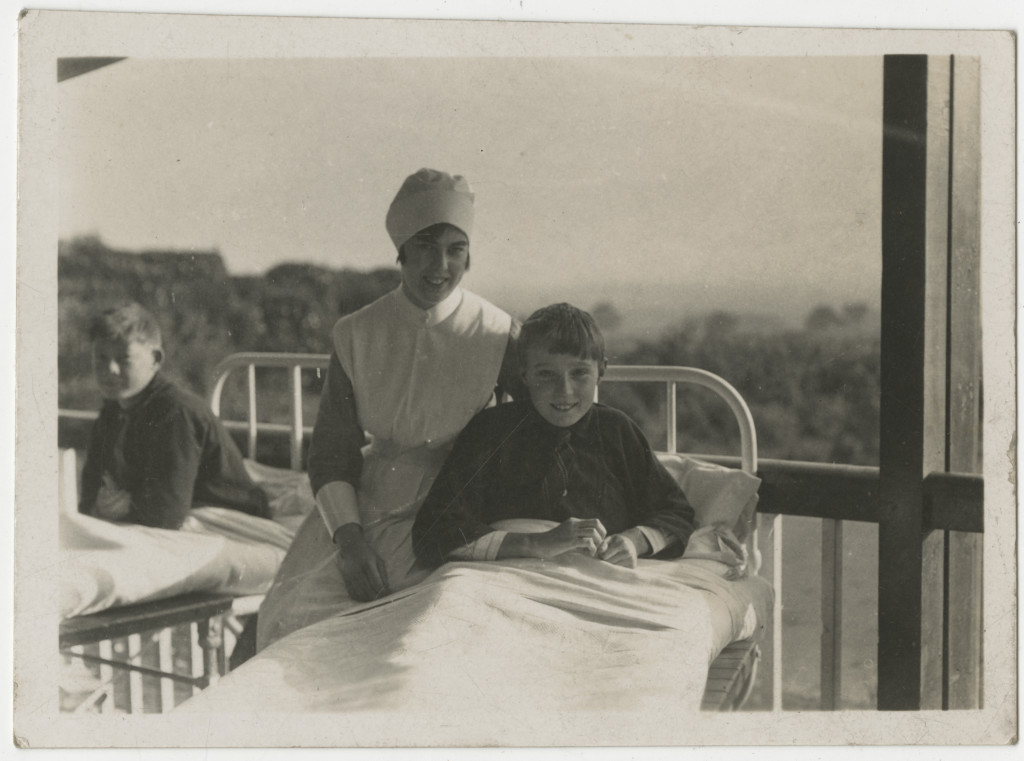

We also worked with playwright Margaret Wilkinson, who used the collection and our research to write a radio play for BBC Four’s Writing the Century. The play was based on the experiences of former Stannington Sanatorium nurse Marjorie Wilson. Margaret established the scene with Marjorie’s reminiscences, and used excerpts from letters within the patient files. The play was a great success, and listeners found the performance very moving. You can read more about Margaret’s inspiration in writing the play in the blog she wrote for us, and you can listen to the play through Audioboom.

We hope to continue further interest in the collection by launching an education resource, now available through our website. In this we have laid out a little summary of the disease, history, treatment and the records at Stannington, and what life was like for staff and patients. This can be used as a resource for teachers to dip into in developing lessons, but also for older students to use for themselves.

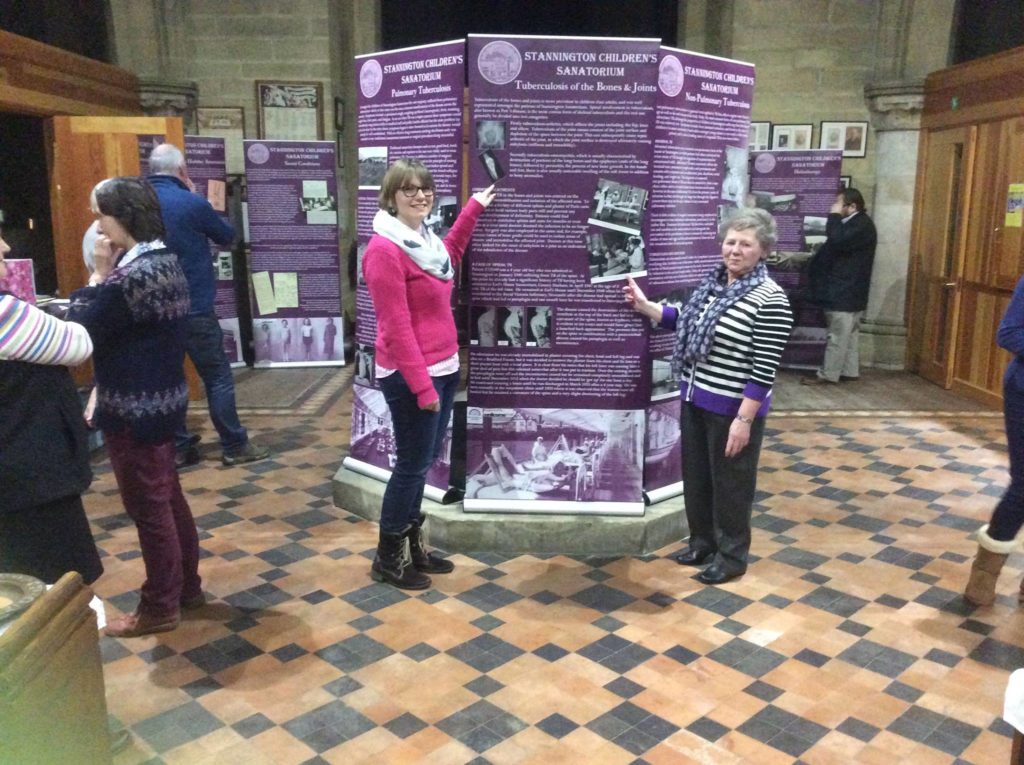

Recently the team have also set up our collection of banners at St Mary’s church in Stannington, with the Stannington History Group. It was a wonderful finish to the project to see them displayed so close to the sanatorium itself, with locals and visitors finding out more about the story of Stannington Sanatorium. We hope to tour the exhibition more throughout this year.

The project has revealed the rich value of the collection in terms of its research potential, as it contains files with detailed medical information and an excellent radiographic record. However it is also rich in the stories of the staff and patients who were associated with the sanatorium, many of whom have recounted their experiences to us during its course. We feel proud to continue to care for the documents, and feel it is important to continue to raise awareness. Far from this being the end of our research with the collection, this is a beginning of a new and more accessible way of learning from them.

The collection itself is housed at Northumberland Archives, and though a hundred year closure period is still in place (from the date of the document’s creation), former patients and some immediate family can still seek permission to access the patient files. If you are interested in accessing the collection for research purposes (we have statistics on the records as well as the files themselves), are interested in loaning our banners exhibition, or have any other queries about the collection please don’t hesitate to contact us at archives@northumberland.gov.uk

If you are interested to know more please have a look at: