Miliary spread is a pathological process involving the widespread dissemination of the tubercle bacilli but the manifestations of this can vary widely depending on factors such as the speed of the spread and the individual’s ability to inhibit further multiplication of the organisms in other areas of the body. Miliary tuberculosis is recognised clinically in patients where there is radiographic evidence of tuberculous lesions of the same age distributed evenly throughout all areas of the lung. This process is most likely to occur soon after the initial infection and is also more common in children under 5 than it is in older children.

It is not uncommon to see miliary tuberculosis develop further into tuberculous meningitis. Whilst on the whole the death rate in Stannington was relatively low, in the pre-antibiotic era (pre-1947) it is noticeable that a significant number of fatalities are as a result of either miliary TB or TB meningitis. The introduction of effective drug therapies altered this situation greatly and the prospects for these patients after this point improved significantly.

Patient 3/1947 was a 12 year old boy from Lemington-on-Tyne who was admitted to Stannington in January 1947 diagnosed with miliary tuberculosis. A report on x-ray films taken in December 1946 prior to his admission describes extensive mottled shadowing across both lungs with hilar shadows much enlarged. The Northumberland County medical officer of health that refers the boy to Stannington gives the following report:

‘States no cough. Mother says he thinks he gets a bit short of breath at times, and that he has definitely lost weight. On examination, slight cyanotic tinge; afebrile, pulse 108. General condition satisfactory (amazing in view of films). Little made out in chest apart from slight impairment of the air entry at both bases. Mass of glands at right side of neck.’

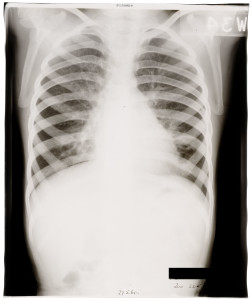

Figure 1 is a chest x-ray taken the day after his admission and the report on it simply reads, ‘extensive bilateral miliary spread’. The extensive mottled ‘snowstorm’ effect is indicative of miliary TB. Strict bed rest is ordered and at this point he also has an enlarged gland at the angle of the jaw on the right side for which UV light treatment is prescribed. Over the coming months the abscess on the jaw is described as discharging freely with brownish pus aspirated from it in June 1947.

09 Jan 1947

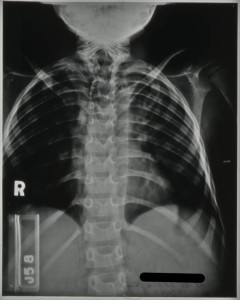

17 Sept 1947

In September 1947 the patient’s doctor suggests that he would be a suitable candidate for streptomycin treatment, which had only recently been introduced at this point. However, having discussed the case further it was decided that he was not suitable as at this point in time streptomycin was being used for very early cases only and patient 3/1947 by now had a long history of TB and was doing very well without it. Figure 2, is an x-ray taken around the time streptomycin treatment was being discussed and the report reads, ‘X-ray shows a little improvement. Each individual lesion is smaller.’

Two months later in November 1947 his condition deteriorates a little and he begins to lose weight and so is again put forward for streptomycin ‘if any available.’ Whilst the attending doctor continues to push for streptomycin over the coming months it is not until November 1948 that the patient receives any. There are continuing disputes as to whether he is a suitable candidate. During this time his general condition fluctuates with periods of weight gain and weight loss and x-rays from April and June 1948 show some improvements, figures 3 and 4 respectively.

13 April 1948

‘Amazing improvement since last x-ray 3 months ago. The military lesions now appear to be resolving: the apices are almost clear. There is now a more homogenous opacity in the left lower lobe.’

04 June 1948

‘still some mottling at the bases, the apices are clear. The more homogenous density at the L base is getting smaller. Azygos lobe on right side.’

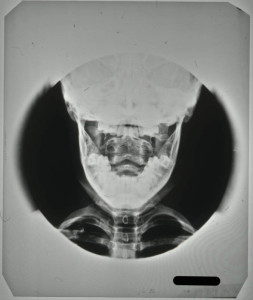

Ultimately the catalyst leading to the decision being made for streptomycin treatment to be commenced appears to be the fact that in June 1948 a swelling over the lower dorsal spine is identified and it is apparent that the tuberculous infection has spread further. It is clear from radiographic evidence in 1948 that there are three spinal lesions: one in the 5th and 6th dorsal vertebrae causing some kyphosis; another affecting the 1st and 3rd lumbar vertebrae causing some deformity; and a final one in the inferior and anterior part of the body of the 5th lumbar vertebrae with some destruction.

All streptomycin treatment is discontinued by May 1949 when significant improvements in his chest are seen and treatment of the spinal lesions is continued with braces and plaster casts. He is eventually discharged in July 1950 wearing a spinal brace and continues to be seen by the out-patients’ service until April 1954 when an abscess in the left iliac fossa leads to him being considered for admission to the Queen Elizabeth Hospital.

Spinal X-ray, 17 Jan 1950, calcifications in the lungs also evident.

Spinal X-ray, 10 July 1950, 4 days before discharge

Chest X-ray, 17 Feb 1950, also showing calcifications in neck glands.

Sources:

MILLER, F. J. W, SEAL, R. M. E, and TAYLOR, M. D. (1963) Tuberculosis in Children, J & A Churchill Ltd.