We can learn a lot about everyday life in the manor by looking at how it was organised. Using manorial documents we can identify individuals and look at what ‘customs’ (rules) they were required to live by, and how they bent or broke the rules that their manor imposed. You could be ‘presented’ before the manor to be ‘amerced’ (fined) for anything from large offences like cheating buyers at your market stall, to not having your chimney in correct repair or cutting back a tree hanging into a neighbour’s garden. Between different manors these rules could be strikingly different.

The customs were upheld by a number of different officials. A Bailiff or Reeve (paid and unpaid versions of the same post) took on the day to day running of the manor. He might be assisted by a barleyman (‘byelaw man’ in charge of upholding the bye laws of the manor), Pinder or pounder (in charge of impounding livestock), lookers (into a particular area, such as fencelooker who examined boundaries and fences), among other roles depending on the needs of the manor. We find evidence of these officials in the manorial documents.

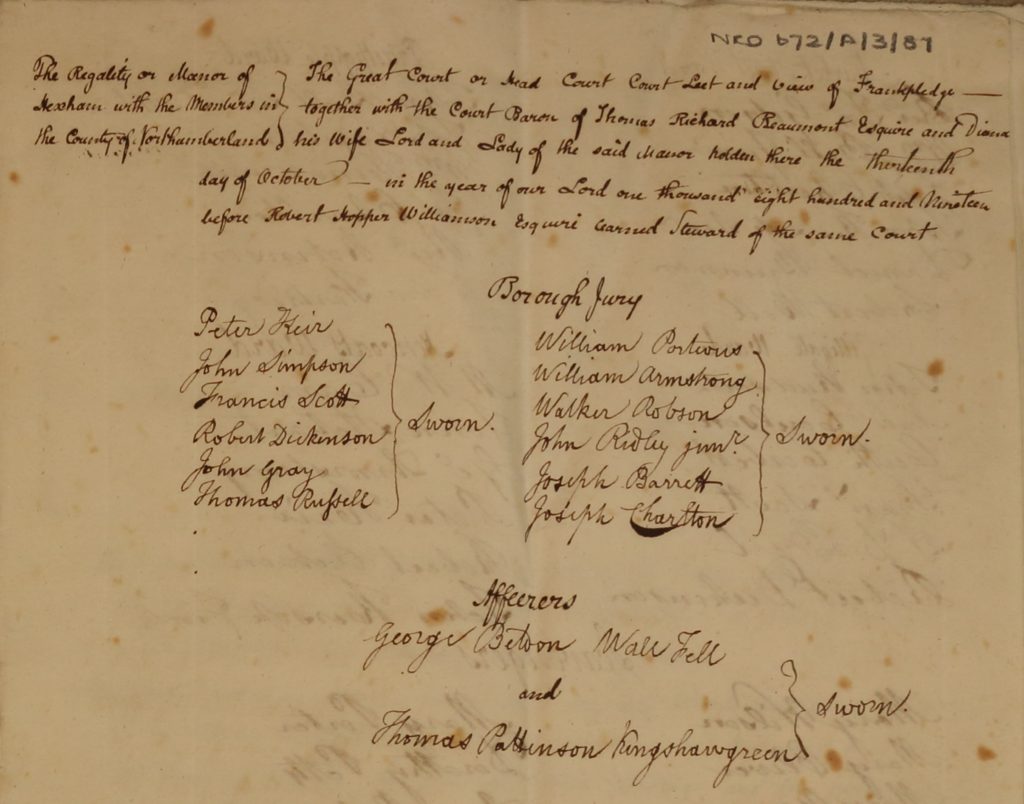

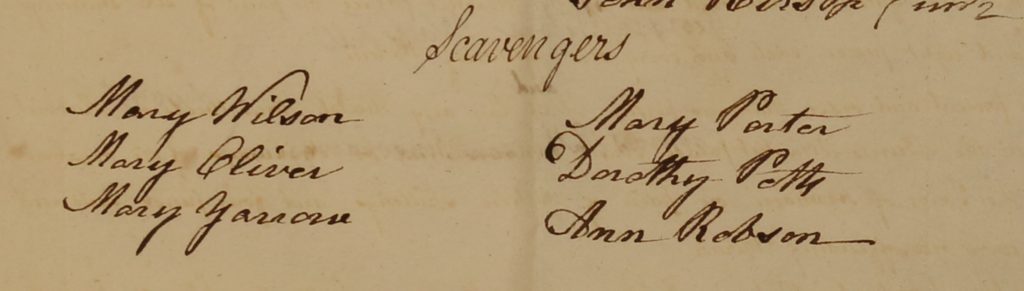

To show how customs worked we will take Hexham manor as an example. In Hexham we have an excellent series of what is known as the Borough Jury books (often spelt ‘burrow books’) from the seventeeth to nineteenth century which give ‘presentments’ (judgements of cases) jurored by a group of the townsmen known as the four and twenty. These books list other roles like the common keepers, market keepers, waits, affeerors, and scavengers. Affeerors were appointed from among the tenants to ensure amercements (fines) were kept fair. Waits were watchmen, often required to sound the hour. The (often female) scavengers swept the market and maintained street gutters in the town, fighting against the piles of rubbish (also ashes, thatch, weeds, gravel, bark and stones) Hexham’s townspeople were presented for leaving.

Other roles can also be found:

Wheras several complaints has been made against George Yarrow for extorting upon the inhabitants of this town in takeing Four pence for calling anything for sale we do therefore present and order that he shall for the future take no more than one penny (NRO 672/A/3/57).

We present and order Joseph Kell, George Batey and John Hills to continue Waits for this town they behaving themselves diligently therein. (NRO 672/A/3/57)

We present and order John Hubbard the younger to take care always to keep water at the pant and allow him for the same one pound one shilling yearly (NRO 672/A/3/57).

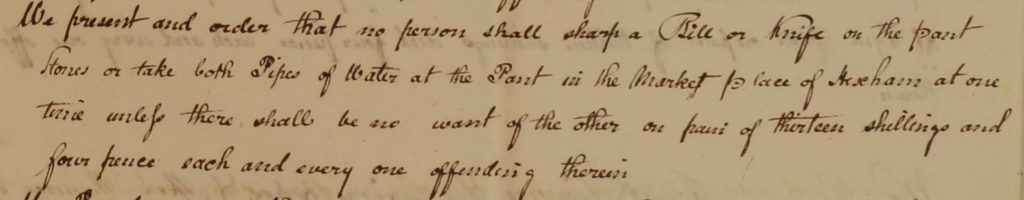

Mistreatment of the water source, such as moving the pipes to divert access, became increasingly common through the books. John’s appointment is presumably related to a subsequent presentment against Hexham’s brewers for using both pipes of water at the Pant, preventing neighbours from their access. Pigs were also not allowed on the town’s streets, and townspeople were amerced for allowing their ‘scabid’ horses on the common (NRO 672/A/3/42). Sometimes vandalism was recorded in the books:

We present Christopher Short for whetting his knife upon the stones of the pant cistern therefore amerced 3s 9d. (NRO 672/A/3/48)

Christopher was among a number of other presented for doing this in 1725. The jury decided that the constable and surveyors should at the town’s charge repair the damage. Preventing sharpening bills and knives on the pant, built in 1703, later became an important custom brought up in each borough book.

The market keepers in Hexham ensured the sales were regulated carefully, and their names are given in the books. They had the authority to search houses in which they believed people were illegally selling corn, or inns which opened before the market time. Haltwhistle market opened at 11 o’clock, but the citizens of Hexham were required to wait until one o’clock, something the books prove they found difficult. At this time a bell would be rung to begin the market, as shown by the following from 1719:

We present Robert Maughan of Todcastle for saleing of corn before the bell ring and therefore amerced 6.6 affeared to 3s 4d (NRO 672/A/3/42)

William Robinson presents himself for buying of corn before the bell ring therefore presents himself into the Lord’s will. (NRO 672/A/3/42)

Selling before the bell was a common problem, and later books show numerous people presented for selling before the appointed time. Selling unweighed bread also brought a number of people to be fined, though at the lesser fine of 1s 8d. All of these stipulations clearly created some resentment among the townspeople:

We present Ann Aydon for abusing Jon Ramsey market Keeper in doeing his office therefore amerced 3s 4d (NRO 672/A/3/48).

This suggests the men and women appointed by the manor may have encountered some opposition to or subversion of the rules they upheld. We might also see competition turning to conflict in the market place, or perhaps just a disgruntled customer?

We present Joseph Craig up on oath made by Samuel Hedley for throwing over the stall and meat standing in the open market belonging to the aforsesaid Samuel Hedley therefore amerced 13s 9d (NRO 672/A/3/48)

Maybe Joseph Craig had felt his cut of meat wasn’t worth what he was charged, as we know there were a large number of people presented for using false weights:

We present Robert Spoone for keeping a false weight, therefore amerced 3s 4d (NRO 672/A/3/48)

We present Thomas Hubbuck for keeping false weights therefore amerced 6s 8d. (NRO 672/A/3/48)

Though keeping false weights seems to have been a common charge, this may have actually been a wider problem in the differences between weights and measures at this time. Often each manor had its own weights and measures that weren’t used elsewhere. Eustace de Vesci gave to the monks on Farne seven horse loads of wheat ‘of Alnwick measure’ (Northumberland County Histories I, 1893, p.334). In 1872 Gulch’s Literary and Scientific Register and Almanack recorded Alnwick, Morpeth and Hexham used a new boll of 16 gallons, while Belford and Wooler used the old boll of 48 gallons. Though this may not have been the same in de Vesci’s time, it does reflect that differences in measurements remained much longer than people might believe. Certainly the frequency that false weights were brought to the Hexham court does suggest this was the case, rather than deliberate fraud on behalf of the sellers.

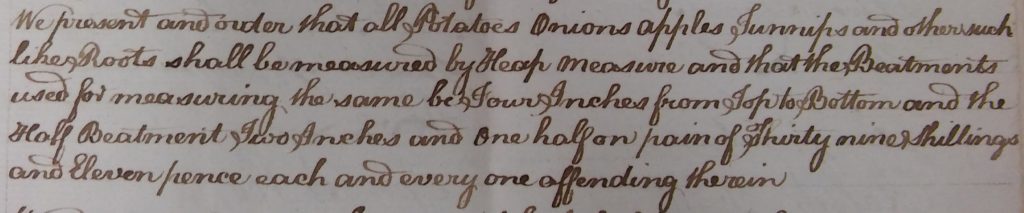

To ensure the weights and measures were regularised Hexham’s Market Keepers were required to check all weights and measures four times a year, and inspect the market each market day. The Borough books specify some of these weights and measures, such as milk sold in the town ‘shall be sold by Bear [beer] measure’ (NRO 672/A/3/60). An order repeated in many of the books decreed that ‘all potatoes, apples, turnips and other such like roots shall be measured by heap measure, and that the Beatments used for measuring the same be four inches from top to bottom, and the half beatment two inches and one half on pain of thirty nine shillings and eleven pence’ (NRO 672/A/3/60).

This difference in measurements also extends to definitions of areas of land as well. Where the rod, perch, furlong and acre are common in later periods we also see terms like bovate and carucate. A carucate was seen as the area of land a team of oxen (or bovate) could plough in a year, which was nominally 120 acres, but has been variously described as between 60 and 160 acres.

Customs did vary greatly between manors and through time, but enabled manors like Hexham to function in their own way. We often see quite specific rules appearing as the activities of individuals created new issues, and one can imagine them happening, such as Chistopher short bening told off for sharpening his knife on the pant cistern. We can see it too at Hartley manor, where bee-hives were banned from inside the town (Northumberland County Histories IX, 1909, p.119), or Haltwhistle where customs specified which weapons you couldn’t bring with you into the market (ZAD/1/A/12). Manors also had customs for specific reasons, such as Longhoughton’s ancient custom in which the court appointed individuals in the village to provide hospitality and stabling for passing members of the Queen Elizabeth I’s travelling household (Northumberland County Histories II, 1895, p.373). Manorial customs show the diversity of behaviour found in and controlled by each different manor, which we can glimpse through the manorial documents like the Hexham Borough books.

Please note NRO 672/A/3/42 dates to 1719, NRO 672/A/3/48 to 1725, NRO 672/A/3/57 to 1739 and NRO 672/A/3/60 dates to 1782.